The restaurant industry is one of the most forward-thinking out there, with top chefs continually innovating to stay ahead of their competition.

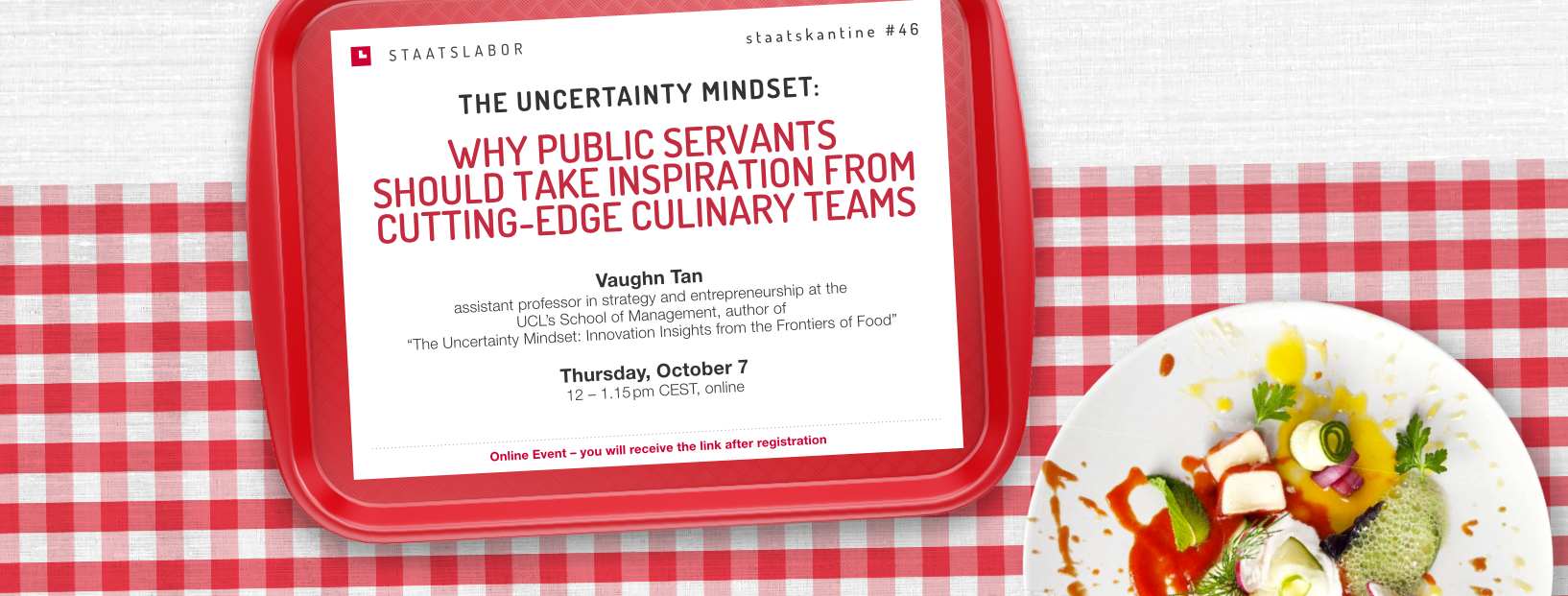

Vaughn Tan, assistant professor of strategy and entrepreneurship as well as founding faculty at University College London’s School of Management, has spent years observing some of the world’s top chefs and their teams. According to him, the most influential culinary R&D teams in the world, including The Fat Duck Experimental Kitchen, ThinkFoodTank and The Cooking Lab, have one thing in common: they share an uncertainty mindset.

Having an uncertainty mindset means acknowledging that its impossible to know in fast-paced, uncertain environment what will work and what won’t and setting yourself up for success by collaborating in radical ways.

Governments around the world are facing increasingly complex challenges in uncertain environments. But they rarely embrace an uncertainty mindset, preventing themselves from responding appropriately to new situations and being innovative.

What can public servants, especially executives, learn from those teams that are at the very forefront of gastronomical innovation?

Below you will find a recording of the conversation as well as an transcript.

At our staatskantine on 7 October, Vaughn Tan shared with us how these teams adapt to change with ease, how they identify the right problems to tackle, and how the underlying organisational design principles used by leading chefs to achieve those results can help governments. We also learned how to develop the capacity for “productive discomfort”, based on Tan’s “idk”, a training tool based on his book “The Uncertainty Mindset” and designed to help you push yourself outside your comfort zone.

Transprict of the staatskantine #46 with Vaugn Tan:

Alenka Bonnard:

Hi, everybody. Welcome and thank you for joining us today. We will today be talking about uncertainty versus risk and what it takes to build great teams that can innovate and thrive in an uncertain world with our guest Vaughn Tan who I will have the pleasure to introduce in a few seconds. I do see a few familiar faces in the audience, but for those of us who are new, I'm Alenka, a co-founder and co-director of the Staatslabor, the Swiss Government Innovation Lab.

When we aren't being together with experts and change makers in government like today, we work directly with government entities on innovation projects of all kinds. If this is something that you might be interested in, please do not hesitate to drop us a line or to stop by at our pop-up office in Berne. It's literally one minute away from the main station and it's really worth it.

It is now my great pleasure to introduce our guest speaker Vaughn Tan. Vaughn, you are a London-based strategy consultant, author and professor at the UCL London School of Management. As a consultant and board member, you work at the intersection of innovation management, product strategy and organizational design with startup and established businesses. And you also work with government agencies and not-for-profit organizations, hopefully soon also in Switzerland. You just launched IDK, it's a training tool for productive discomfort. It's a set of cards and we just ordered a few of them, we're very thrilled.

And last but not least, you are the author of The Uncertainty Mindset a book about designing organizations that are resilient to and benefit from uncertainty. It's a really, really cool book. First of all, it's about food also, it's also about food, culinary R&D, which is in my opinion, personally fascinating, and it's a lot of fun to read. But then it's also very daring and pretty radical. I'm sure you will talk about it. So I can just recommend it to get not only one copy, but one for you and then the friends you will want to read it because it's just an amazing book. So now I will be very short, stop talking now. Thank you so much for being with us today, Vaughn, it's an honor and privilege to host you. Over to you.

Vaughn Tan:

Fantastic. Thanks very much for that very generous introduction. I love it when people recommend the book and recommend buying more than one of them. So as Alenka said, what I'm going to talk about today is essentially the relationship between uncertainty, adaptability and innovation and I'm also going to highlight some areas in which these issues are important, especially for governments, but they're generally important for businesses, not-for-profits, for profits.

They're important for organizations no matter what area they're in because uncertainty is becoming a bigger and bigger part of the world that we live in. So before I get started, I wanted to say a few things about who I am and what I do. I'm a researcher and a consultant as Alenka said, and the things which I focus on primarily are innovation and uncertainty. I try and understand how organizations become more innovative, I also try and understand how they can adapt better when they're facing uncertain situations.

Before this, I worked with the product team at Google, so we were in a very changing environment and a very rapidly changing industry, very uncertain, and a lot of my initial insights into how to design organizations that are good at innovation and adaptation came from looking at Google. Since then, I've moved on. I went to do a PhD and then now I teach, I'm a professor of strategy in the school of management at University College of London.

Another thing about my focus on innovation, especially in uncertain situations, is I end up working a lot with organizations that are public interest or not-for-profit or government organizations. So I worked with the Wellcome Collection in London, with the Region of Skåne, which I always pronounce incorrectly, in Sweden, with the Area de Conservación Guanacaste in Costa Rica, with the Data Protection Foundation in the UK, and with Rethink Food, which is a not-for-profit based out of New York.

And one of these in particular, the Area de Conservación Guanacaste, I'm going to tell you a little bit more about towards the end of this talk. So to go a little bit deeper, the things which I try and think about and I try and help people do is to figure out how to rebuild or build organizations so that they're more innovative especially in situations that are truly uncertain. And though I work and study startups and established companies, a lot of my field research as Alenka pointed out has been conducted in the world of cutting edge culinary R&D teams.

These are research and development teams that look a lot like, if you think about it, the kinds of R&D teams that come up with new pharmaceuticals or new materials that can be used in making new products, except they happen to be working on food. A lot of the insights from these kinds of teams, I think can be applied more generally, not only to other for-profit organizations, but also to governments as well. A lot of the ideas that I'm going to share with you today is from that research and that research is in the book that Alenka was very kind to promote for me which is called The Uncertainty Mindset.

And it's a book about how the best restaurants in the world design themselves to be innovative and adaptable and what other types of organizations, including governments can learn from them. I'll share some of the main ideas with you today. So just to take one step back and give you some of the takeaways that I want you to have from today. The first one is that I think it's often a misconception that governments and businesses face very different problems. I think they face different areas in which they need to work, but the problems they face are broadly similar.

Both governments and businesses increasingly need to adapt to uncertainty and they also need to do new things in order to adapt to uncertainty. The problem that they face that is a common problem is that adapting to uncertainty and innovating are both really, really hard and very few governments or businesses do them well. We hear a lot about the ones that do do it well, but they are in the very small minority no matter whether you're talking about governments or businesses.

The main takeaway that I want to leave you with today, which I'll unpack during the course of the talk is that a lot of the time, people, leaders in governments as well as in business, they try and get rid of uncertainty. But uncertainty is not something you can get rid of. It's just something that happens to you. Acknowledging uncertainty makes organizations more innovative and better at responding to uncertainty and I'll explain why later on.

The key here is that responding appropriately to uncertainty and innovating effectively actually have the same root. When you recognize and you accept uncertainty for what it is and you bring it into your organization, you are able to have what I call the uncertainty mindset. This is a way of dealing with uncertainty that is productive, that helps you and your organization learn and therefore helps you and your organization figure out how to adapt to unexpected situations and also to come up with new ideas.

So today's agenda, three parts. I want to tell you about the difference between risk and true uncertainty and why it's so important to know the difference when you are taking action. The second thing I want to talk about is that connection that I just mentioned about how uncertainty can actually increase innovation and adaptability. And then I want to leave you with some concrete ideas about how to use uncertainty as a tool for making your organization more innovative and more adaptable.

So the first part, risk is not the same thing as uncertainty. I think risk and true uncertainty are definitely not the same thing. And this has really serious implications for everyone but especially for governments. There is a long history, especially in economics of formally distinguishing between risk and uncertainty. And both of them actually mean that you don't know the exact future outcome of the world. Now, what is the actual difference between the two?

If you are in a situation of risk, formally, you need to know all the possible outcomes and all of their probabilities. This makes risk mathematically calculable. If you're in a situation of uncertainty, you're in a situation where you don't know all the possible outcomes or you don't know their respective probabilities. What this means is true uncertainty is not mathematically calculable.

If you think about what this implies for the situations that governments tend to face, they are usually in a situation where they don't know all of the possible outcomes that their actions can take, they don't know all the definitions of success that they need to pursue, they don't know how likely these outcomes are. Governments especially are operating in situations of great uncertainty, not in usually only situations of risk.

Now, the problem is most people and organizations—and I include governments in this—they continue to mistake risk for uncertainty. They always talk about risk management. They don't really talk about or think about how to think about uncertainty in a way that lets them adapt to it as the situation changes. And the problem with that is that when you mistake a truly uncertain situation for one that is risky, the outcomes are usually at least not good, but at worst can be really terrible.

A lot of these examples are things that we know about because we've lived through them. The financial crisis of 2007 to 2008 was caused by banks as well as regulators who thought that they were in a risk situation in terms of managing the risk from very complex financial derivatives. In fact, those complex financial derivatives were so complex and so interconnected that a small part of it going down—Lehman Brothers—led to a large part of the world financial system going down.

But even closer to home and more proximate in time, much more recent for us, is COVID. In early 2020, when the situation began to emerge in China and then eventually everywhere else in the world, a lot of governments were thinking about the situation as something to be risk-managed rather than something where there is a huge amount of uncertainty about how lethal this is, how fast it spreads, whether or not there'll be a vaccine, whether there's a therapeutic, whether there would be new variants. None of this was known, yet the situation was not treated as an uncertain situation to be managed as an uncertain situation. Instead, it was treated as a risk situation.

We're still living with the results of that. Many countries are still in partial lockdown, the economies of many countries have been devastated and still we're not through the COVID situation. Partly because I think it was treated as a risky situation to be risk managed, rather than an uncertainty situation to be thought of and managed as an uncertainty situation.

So what is the difference between how you need to act as an organization or as an individual in a risky situation and an uncertain situation?

I think a risky situation calls for very traditional ways of thinking about taking action: Rigorous cost benefit analysis and you're supposed to take action that maximizes expected outcomes. To go back to the definition of risk: Risk is when you know all the possible actions you can take, all the possible outcomes that can happen and how likely each one of those is to happen, the probabilities. If you have all that information, you can make the kinds of decisions that risky situations require.

But if you don't have that information, how can you do it? And if you cannot make the correct decisions because you don't have all the information, you can make inappropriate, even disastrous decisions. And this is the problem that we saw with Coronavirus. A lot of the early slowness in how countries as well as global organizations dealt with Coronavirus were partly because they were trying to mitigate risk out of a mistaken understanding of the situation as being risky.

They thought they knew all the possible outcomes and they didn't. One of the things they were trying to do was minimize the impact on world trade, world travel. They slowed down the process of announcing a serious pandemic and they slowed down the process of limiting world transport because previously previous pandemics had different characteristics that were incorrectly applied to this particular situation.

Now, what if you're in a situation of uncertainty. Uncertain situations are very different. You don't know all the possible outcomes, you don't know all the possible actions, and you don't know how likely those possible outcomes are. Uncertain situations need organizations to be able to learn, be willing to fail, be able to change as situations change and, very importantly, be able to do new things that have never been done before. Uncertainty requires both innovation and adaptation, and as I've said before, these are exactly the things that are really, really hard for all organizations, whether they're businesses and governments to do, right?

So if you look at this list of things, learning, the willingness to fail, the ability to change how situations change, the ability to do new things that have never been done before. Literally every organization of any size has problems doing this. And so the question is: How do you use uncertainty, which causes the need for all of these abilities, to actually give you the ability to do all these things? This is that weird, counterintuitive loop I mentioned at the beginning.

Uncertainty both requires all of these difficult-to-have abilities and also gives you the ability to have these abilities. I'll explain a little bit about that right now. The way uncertainty can increase innovation and adaptability is a little bit counterintuitive or difficult to think about, I suppose.

We should start with the idea that innovation simply means doing something new. Doing something new necessarily means doing something unknown. Doing something unknown means that you are uncertain, you simply don't know how it is that you got to do it. In fact, you often don't even know what the successful outcome truly looks like.

What this means again, is that if you want to do anything that's innovative by definition, you are trying to do something which is uncertain, not something which is risky. We know that, as businesses and as governments, we need to be more innovative. This means we have already said to ourselves we need to do things that are uncertain.

Now combine that with the fact that there is an external need to do this as well. The world environment is becoming more and more uncertain as it becomes more complex and interdependent. Both the global financial crisis as well as the Coronavirus pandemic have shown that the uncertainty inherent in any particular problem—like complex financial derivatives or a new virus—becomes magnified by many tens or hundreds or even thousands of times, if that uncertainty is embedded in a system where the connections between different parts of the system, whether they're banks or countries, is complex and highly interdependent.

This is the world we live in today. We've built a world that is inherently complex and interdependent, and therefore the world is more prone to being uncertain. We have examples from right now. We're in the middle of a shipping and inventory crisis around the world, not just in the US and the UK because we built this very, very complex global supply chain that is actually very fragile and prone to uncertain behaviour because of its complexity and interdependence.

Any single perturbation in this supply chain ripples throughout and magnifies itself, creating the kind of uncertainty that we're seeing today. But it's not just that. Long-term, it's not just the human world that we live in that's becoming more complex and interdependent and more uncertain. We already live in a highly complex and interdependent environment that is the natural environment. And our perturbation of it is causing these climate related extremes that are have already resulted in massive economic disruption in the last few years. Uncertainty from climate is going to become more and more pronounced in the future.

If we're in a situation where innovation is uncertain and the world is becoming more uncertain and requires innovation and adaptation to it in order to be successful, we're also in a situation where innovation itself almost always produces uncertainty. If you think about an innovation like Facebook which started as a social network, that then became a way for people to see new information, what's happening there is the innovation in how people gather media and absorb content is disrupting the traditional media agencies like newspapers.

The flip side of this is that uncertainty is almost always managed by doing something innovative. When the situation changes in uncertain ways that you couldn't have predicted before, the answer or the solution to solve the new problem is almost always a solution that didn't exist before. Again, we come back to COVID. Before the Coronavirus pandemic, we had a very traditional method for developing vaccines and for validating and then approving vaccines and then distributing them.

All of a sudden, you've got huge uncertainty from Coronavirus, the entire world is suffering from it, all the ways of doing things like making vaccines, approving them and then distributing them no longer work. They simply are not going to be adequate. What do we do? As an entire global community, we come up with new ways of doing things. mRNA vaccines, a brand new pathway for building a vaccine, entirely new methods for doing the initial development as well as the assessment, trial, evaluation, and approval of those vaccines. Completely new ways of thinking about organizing of mass vaccination at scale and at speed that we've never done before.

Innovation is a way that we solve the problem that uncertainty creates for us. What I'm trying to say is that innovation and uncertainty are related to each other. Innovation causes uncertainty, uncertainty causes innovation and both of them need to be seen as two sides basically of the same coin.

Innovativeness and adaptability are two sides of the same uncertainty coin. You cannot get rid of uncertainty because if do, you get rid of innovativeness.

You also can't get rid of uncertainty because it is just there. We live in a complex and interdependent world. It is not something that we can get rid of, unless we go back to being an uncomplex, unconnected world. If you believe my assumption that uncertainty is both the cause of the need for innovation and adaptation as well as the thing that gives you the ability to innovate and to adapt, then the question is: "How does uncertainty work as an innovation and adaptation tool?"

The first thing to say about this is that innovation and adaptation aren't always necessary, but when you need them, you really, really need them. Increasingly we really need government and business organisations to be both innovative and adaptable. This is about not just innovation at the level of products, but also innovation at the level of how we organize ourselves and how we think about structure and design of organizations. An example of this is Operation Warp Speed, which you may recall was an American, Trump-originated program for rapidly accelerating the development of Coronavirus vaccines.

It actually worked very well in accelerating the vaccine development, although it may not have worked very well in doing the distribution part of things. But Warp Speed basically represents a real innovation in how you organize the funding and the actual work of doing vaccine development and approval and it also represents an innovation in how you fund it. So all of these are organisational innovations that are built to adapt to a situation that was caused by uncertainty.

If you think about how to do this innovation and adaptation, what it means is that people and organizations need to be willing and able to learn and change. If the vaccine developers, if the government agencies that did the approvals, if the funders, if the government as an overarching organization, had not been willing to do things differently, Warp Speed would not have been possible. But because they were forced to do something different, Warp Speed became a reality and was able to help us move very quickly to develop a new vaccine.

Now, the key thing here is this willingness and ability to learn and change.

Even though we all know conceptually that learning and changing is really important as a skill, we actually find it very difficult to do it. Learning and changing always entails, both at the individual level and at the organizational level, being in a situation of not knowing and uncertainty. You cannot learn something unless you admit to yourself first that you don't know how to do it.

You cannot do something new unless you admit to yourself first that you don't know how to do it and you may not even know what the successful outcome necessarily looks like. This is the problem. If learning and change are so dependent on embracing uncertainty, the problem is actually that people and organizations instinctively avoid uncertainty. The reason for this avoidance of uncertainty is based in fear.

It's a deep, visceral, emotional reaction. Our reaction to uncertainty is often like an allergy. At first you don't know why it happens, it just happens. That's really fatal for organizations that need to be innovative and adaptable. Given that uncertainty is something that people and organizations are viscerally, emotionally afraid of, the problem is that uncertainty is the only way that people and businesses can learn and change.

How then can you build an organization that can handle uncertainty, that can adapt and innovate? You need to intentionally inject uncertainty into your organization. But this uncertainty needs to be designed so that it lets the people in the organization and the organization as a whole learn how to learn and change. It must also be done carefully so it doesn't trigger an organizational allergic response. If you overload the organization, it will simply reject the uncertainty the same way you have an allergic response. So the goal really is to create uncertainty inside your organization but design it to be productive and prevent the organization from rejecting it.

And so three principles for doing that. I'm going to summarize them and then I'll talk about each one of them in turn.

The first one is to really think about experimentation, running pilot projects. I'm going to talk about some parameters for designing these to be effective. The second one is to make sure that you're designing for learning. There's a twist to this, which I'll also say a bit more about later.

And the third thing is to load progressively. The metaphor I want to give here is a physical metaphor. If you go to the gym for the first time ever and you have never lifted weights before, you do not try and lift 200 kilograms all at once, what you do is you gradually build up and this is what I mean by loading progressively. If organizations or people are exposed to too much uncertainty all at once, they reject it—it's analogous to how someone who has never lifted weights, if they try and lift 200 kilograms all at once, they may succeed temporarily, but they will probably injure themselves maybe never want to try again.

The key with loading progressively is to introduce uncertainty slowly and with some design parameters that I'm going to talk about right now.

Now the key thing to say about the design parameters for an experiment that creates productive discomfort is that it must have three properties and all of these are necessary. The experiment must be slightly but not massively beyond the organization's current ability. It must be designed to produce desirable learning even if it doesn't succeed. This part's really important. Most people don't design experiments so that regardless of whether it produces the outcome that you expect, you still learn from it, and this is what an experiment to create productive discomfort needs to have.

And the third thing is, it must be real. It doesn't have to be big, but it can't be fake. The experiment must have real and important consequences for the organization so that the people who are involved in the experiment feel that there is a real reason why they're doing it. The organisation isn't just pretending to not know how to do something, it actually doesn't know.

I want to talk a little bit more about designing for learning by making sure experiments benefit you even if they don't go as planned. Here's an example from a restaurant called Noma in Copenhagen.

What you see on the left was something that they started doing in 2011. They were trying to figure out whether they could make soy sauce or use the same process that was used for making fish sauces in Asia, and for making garum in classical Rome, and apply that to waste products from their kitchen. So not only to do it for the Noma kitchen itself, but to learn about whether you could make a product out of waste products to reduce the amount of food waste that is going back into trash. And so what you see on the left is their first experiment which didn't work. Many of their subsequent experiments failed too.

But because they were designing the experiments so that even if they failed to produce the fish sauce that they were trying to produce, they were still learning about the parameters for doing things successfully. The result of that ongoing record keeping and designing of experiments so that you learn even if you fail: After seven or eight years, the team there had a very deep knowledge of how to do things well that was based on learning from experiments designed to teach despite failure.

And it's turned into a major asset for the restaurant in terms of how they make new dishes. A lot of their food is now based on fermentation products. They've also produced a range of other products as a result of that, for instance a book that captures a lot of the knowledge they developed over the years of failed experiments.

This may seem very far away from what governments do, but the key thing here is to remember: Whenever you try something where you don't know if it will work or not, the most important thing is to design that experiment so that even if it doesn't work the way you hope, you can learn about why the process didn't work, you can learn about what resources you should have had that would maybe have made it work, you can learn about what things you did concretely that you can say concretely made it not work.

These are all ways of learning that helped you figure out what the next experiment that might work would look like. And you've got to keep track of all these learnings. It's a different way of thinking about how to run an experiment that is quite important.

The third thing that I mentioned is loading progressively. This idea can be very simply put: Start very small. What that does is limit your downside exposure. It limits your reputational exposure in case you fail and it also allows you to try the experiment in a way that reduces the kind of emotional fear of failure.

If that small experiment works, not only do you have insight about how to design the next bigger experiment so that it works even better, you also have proof that the next bigger experiment is worth doing. This idea of starting small and then experimenting in bigger and bigger ways is how you get past the problem of big organizations that are really afraid of failure killing an idea before it's had a chance to show that it actually works.

So I want to give two examples of combining these three design principles for experimenting in a way that is productive, that encourages learning and change. One example is from the world of food and then one of them from what I would call it very broadly the government and public sector.

Some of you may have heard of an organization called MAD. It's an organization that was initially started by René Redzepi at Noma. It's now turned into an interesting, difficult to describe organization that runs talks, creates a community within the global food industry around thinking about sustainable change. Not only sustainability from the perspective of business models for the restaurant industry, but also sustainability from the perspective of agriculture, sustainable agriculture, reduction of food waste. And also thinking about sustainability from the perspective of changing the way human relations and labor relations works in the food business so that it's less damaging to the people who work in it.

This is now a global community that is incredibly influential, but it's important to remember that it started from one single experiment that was very small. Today MAD is an independent organization. But when it started in 2011, it was not even an organization, it was an idea that Rene and his team had. They were running a restaurant, they'd never run a conference before.

The idea was: "Why don't we bring together a bunch of people that we think are interesting and ask some questions that usually chefs and people in the food business don't ask?" So that was really difficult for them because they've never organized a conference before. In doing this first experiment, they learned a lot of things that regular conference organizers already know. There was the possibility of failure, for sure, but it didn't fail.

In fact, the first one was such a massive success that they actually did many more. They did them about once every two years or so. And not only did they do many more MAD symposia, but in each one of them, they were experimenting with ways of engaging a bigger and bigger community, with working with different people which represented different skillsets. They also started doing other things as well, other experiments.

Think of the first experiment as MAD 1, which is let's do a conference. Each of MAD 2 through 6 was an experiment with increasingly difficult things to think about and talk about, and with different ways of organizing the symposium. Along the way, MAD also experimented with different formats and different products. They built VILD MAD, an app that allows people to learn how to go out into the world around them and see food that they don't normally think of as food and to use it safely.

They're basically experimenting continually with different ideas of what it means to do something new. Some of them didn't work very well, some of them did. The ones that did, they expanded. And eventually they got to a point that you would never have been able to imagine them getting to in 2011. They've just started MAD Academy, a public-private funded school that brings together a lot of the things that they were doing in these seminars, apps and the small talks.

Today you look at MAD and you think, "They did all this amazing stuff." But where it actually started was with one experiment, very small. There was a lot of uncertainty involved. There was downside risk for them for reputational damage if they failed. But because MAD 1 worked, they gradually experimented and gradually scaled up each time, doing experiments designed to teach them even if they failed. And eventually they got to the point where they're doing things that nobody would have expected them to be able to do 10 years ago. They got there by progressive loading.

Now I'm just going to take a few minutes to talk about something which feels more like a public sector thing. I mentioned before that I do a bit of work for the Area de Conservación Guanacaste. Today, if you look at it, it's a huge world heritage site, 169,000 hectares. It's very large and covers four contiguous tropical ecosystem types. This allows for biodiversity conservation and research at a level and in a way that is not possible in a lot of other places. But ACG also provides a bunch of other things: environmental amenities, it sequesters carbon, it creates a wide range of jobs, it innovates in the structure and management of the park, it provides primary resources because it's a managed ecosystem extraction program, it does cultural protection and enhancement, land protection, reforestation, and academic research. If you look at it today, you might think, "How did they figure out how to do all of that?"

And the answer is actually very similar to how MAD went from a single tiny conference for 200 people to something which is now a global community of tens of thousands of really influential chefs. And the way they did it was they started with one small experiment. In 1966, the Area de Conservación Guanacaste was a thousand hectares at Santa Rosa, a single park. And over the course of the last 50 years or so, probably 40ish years when it really started growing, there was a sequence of progressively larger experiments with stakeholder relationship management, ways of working with local and national government, how to design conservation programs, funding structures, redesigning the organizational structure of individual parks and the overall park administration.

That process of gradual experimentation started small to limit downside exposure. But each experiment allowed them to learn even if they failed. They were able to gradually build on successful experiments to become a multi-stakeholder, very decentralized, very horizontalized administratively run conservation area, funded through public-private collaboration.

This is an especially staggering achievement when you think about how ACG is located in Costa Rica, which is very progressive but still a government that in almost everything else is very much centralized and hierarchical. That ACG is doing this and has been successful for so long is testament to the idea that you need to introduce ideas that are experiments that are designed to be productive, that teach you even if they fail gradually so that you can use success at a small thing as proof and justification to do more and more stuff, gradually building on things until you get to the point where you are doing something really amazing that people look at and think, "This is great. I wish we could do that too."

We can talk more about this when we do Q&A, but I just wanted to close off by saying the three main principles are 1) experiment often, 2) design these experiments for learning even if you fail, and 3) load the experiments progressively. This third part may actually be for governments the most important thing. Always start so small that the bosses or the voters don't notice you're doing anything yet and only reveal it when you've got enough success that you can show them that this works and then they can get bigger and bigger after that.

So I'm just going to wrap up very quickly. The main takeaways are risk is not the same thing as uncertainty, it's really bad if you mistake them for each other. Uncertainty makes innovation and adaptation really important, but uncertainty—recognizing, accepting and incorporating it into how your organization works—is also a precondition for being innovative and adaptable. So the two things are connected to each other. And in order to make your organization more adaptable and more innovative, you need to inject productive uncertainty into your organization without triggering an allergic reaction. We can do that by experimenting often, designing for learning, and loading progressively.

So I just wanted to do a quick plug. A lot of these ideas are expanded in much more detail in the book that Alenka mentioned. You can find out more about it at uncertaintymindset.org.

Another thing which I've alluded to is that the real obstacle to innovation and adaptation is recognizing and overcoming what is usually a personal individual fear of not-knowing. One way to become more innovative and adaptable is to intentionally go into a situations that teach you to manage the discomfort that comes from confronting uncertainty.

I've built a tool to help people do this—the IDK cards that Alenka mentioned. This is a tool that looks like a game, but has a serious objective. It's meant to help you repeatedly put yourself in situations where you're uncomfortable in a way that helps you learn and grow. The idea is that you learn how to deal with the emotional feeling of being uncomfortable in low-stakes situations, so that when you're in a situation where being uncomfortable has really high stakes, you don't avoid it and you don't have an allergic reaction to it. You can find out more about this at productivediscomfort.org.

And I would love for you all to get in touch. Like Alenka says, I do advisory work for not-for-profits and governments. I love working with them because I think they've got really big, good problems to solve, I would love to do something so feel free to get in touch. And I think at this point I would like to turn it back around to the rest of our team to do whatever they do for Q&As.

Alenka Bonnard:

Thank you very much Vaughn.